Horses, Nazis, and Romance: The Story of Human Heart Catheterization

Psychotic surgeon sufficiently solves a stifling situation

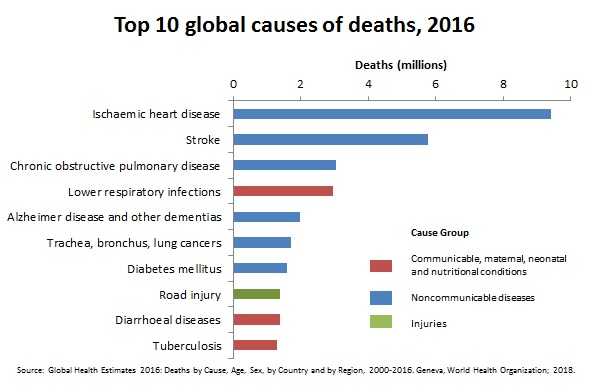

In 2016, the WHO reported that 56.9 million people died (bummer). 54% of these deaths were distributed among 10 causes, with 27% dying of ischemic heart disease or stroke, the top two killers.

Death is pretty lame, which is exactly why Werner Forssmann decided to do something about it. Werner was many things, including a physician, a POW, a Nobel Prize laureate, and, yes, the second-most infamous Nazi doctor in history (which, categorically, makes the man a piece of crap).

This story has nothing to do with his lame politics, and more to do with how he solved an enormous global problem. Werner, born in 1904, grew up in a world not entirely unlike our own. The first X-ray had been performed in 1895, and doctors all over the globe had been slowly and ecstatically zapping themselves to death exploring the medical benefits of being able to see inside the human body. However, we were still unable to see inside the human heart.

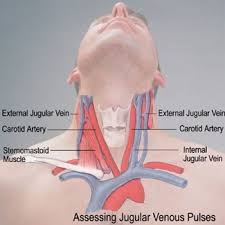

Forssmann had heard of Claude Bernard, a brilliant 19th century physiologist, most famous for establishing the use of the blinded experiment, and his heart catheterization technique, performed first in 1844, on a horse, using a glass thermometer, and inserted through the jugular vein and carotid artery.

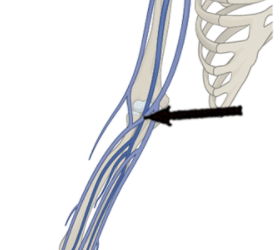

Horses are bigger than people (now you know), and their veins and arteries are proportionately larger. Things don't always work the same in horses and humans (shocking). In 1929, a year after he had started studying surgery, at the age of 25, Werner figured that if they can do it through the neck on a horse, it's probably good enough to perform on an un-anaesthetized human through the cubital vein in the arm.

The young bright-eyed Werner ran his idea by the surgical department chief who forbade trying it out in the interests of, y'know, not murdering people. Reportedly, Werner, was one suave proto-fascist. A real smooth operate-Hérr. In his own (translated) words, he began to "prowl" a young surgical nurse named Greta Ditzen like a "sweet-toothed cat around a cream jug." He charmed her over the course of weeks, describing his ideas and how he had been forbidden from trying the procedure on a human being. As Werner had intended, Greta volunteered to sneak into the hospital with him, give the then-intern access to the tools he needed, and be his first live test subject.

Ever since childhood, I have been told to check both ways before crossing the street, and never to submit to voluntary unauthorized experimental surgery, no matter how good-looking the intern that wants to perform it is. Ms. Ditzen was never hit by a car, so she had at least half of this information as well. If you are one of the 25% of Canadians aged 20-79 with hypertension, you should probably thank her parents for neglecting to teach her the second half.

The twosome snuck into an operating room while the hospital was relatively unoccupied by staff. Greta retrieved the tools (including the 30-inch tube most likely to lead her to her maker), sterilized them, and Werner tightly restrained her to the operating table, so that she couldn't move and "wouldn't fall over from the effects of the local anesthetic" applied to the entry point in the arm.

At this point, Werner injected himself with the Novocain and began to insert the catheter into his own arm. The bewildered nurse watched and struggled to get free of the restraints. Once the catheter was deep enough that the true nature of his plan was established and there was no going back, he freed Greta and, with the catheter still dangling from his arm, they made their way down two floors to the hospital basement, where the X-ray machine was (necessary for guiding the catheter to his heart and documenting the results).

They commandeered the staff operating it, except for one objector who Werner had to physically pacify, as the objecting doctor (also a friend of Werner's) tried to tear the catheter out of his arm. With the help of his involuntary helpers, Werner was able to successfully guide the catheter to his own heart.

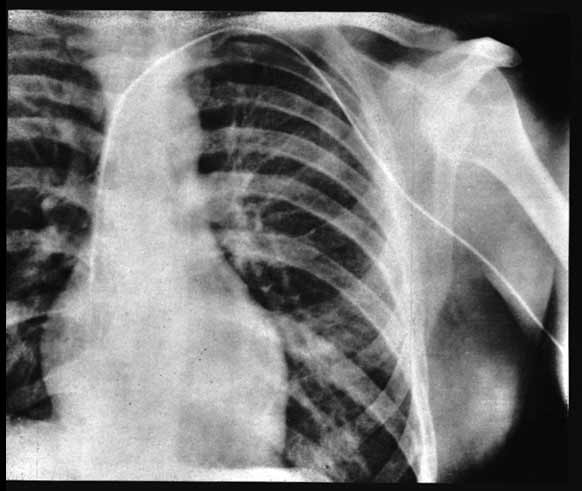

The ordeal was messy and dramatic, but it left us with this:

Undeniable proof of the first successful human heart catheterization.

Werner found it difficult to find a cardiology department to work for after these events (wonder why), and would move on to an area of medicine where people weren't as stuck up and risk averse (urology). He was recognized for his accomplishment in 1956, when he won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

I'm assuming no one made it this far in my way-too-long post, but that is one of my favourite stories from medical science, and I hope you enjoyed it too.